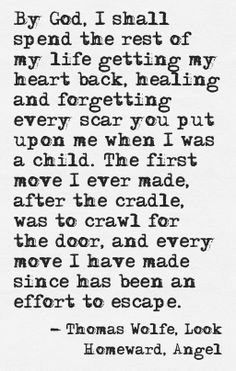

Thomas Wolfe as a young man Thomas Wolfe as a young man I don’t know when my Mom, Edith, first read Thomas Wolfe’s Look Homeward Angel or if it was the first of his four autobiographical novels that she read. She read them all, including a fifth book, The Hills Beyond, that is comprised of essays, a one-act play, some short stories, and a novella. At times she seemed obsessed with him. I’ve always wondered why. When she began traveling after I left home in the 1970s, his memorial in Ashville, North Carolina was one of the first places she visited. A quarantine during the pandemic gave me time to reread those of his major works that I read years ago, plus the others I hadn’t, and figure out what attracted her. Wolfe wrote the first two novels, Look Homeward Angel and Of Time and the River, with the help of his editor, Maxwell Perkins, whose character he names Foxhall Edwards in the novels. His last two novels, The Web and the Rock and You Can’t Go Home Again, were compiled posthumously by his last editor, Edward Aswell. The character and location names and histories change from the first two in these novels—for example, Eugene Gant becomes George Webber and Altamont becomes Old Catawba—but the four novels are a continuous story of Wolfe’s early life and growth as a writer. Much of the books are nostalgia and remind us of Marcel Proust’s three-part series In Search of Lost Time. I used her 1960 copies of The Web and the Rock and The Hills Beyond. Copies of the others disappeared when I was in college and she loaned them to a friend of mine, which were never returned. I tried to buy copies printed closer to the time of publication in the 1930s and bought one in Ashville at the Thomas Wolfe Memorial. I suspect that she was introduced to him while studying for her General Educational Development test (GED) through the American School of Correspondence in the late 1940s while awaiting my birth. Her parents took her and her twin sister Ellen out of school after the tenth grade to help the family out. But more on that later. It was helpful to consider the frames of reference through which Edith may have read Look Homeward Angel in the late 1940s and again later. I don’t know how many times she read it, but once was in the 1960s. As Mom read the books, I think that Eugene’s and sometimes his sibling’s descriptions and emotions often reflected her own.  Photo from Mom's 1939 family reunion Photo from Mom's 1939 family reunion The First Novel and Family Connections The front flap of my Grosset and Dunlap edition Look Homeward Angel (published during WWII) has this New York Times quote: “Wolfe has the ability to find in simple events and in humble, unpromising lives the whole meaning and poetry of human existence.” And “…a book to be savored slowly and re-read.” Who knows why families make the decisions they do. Wolfe felt that every action creates a ripple similar to Jungian psychology, common at the time, that part of the unconscious mind is derived from ancestral memory and experience and is common to all humankind as reflected in the first paragraphs of the book: “Each of us is all the sums he has not counted: subtract us into nakedness and night again, and you shall see begin in Crete four thousand years ago the love that ended yesterday in Texas.” “…our lives are haunted by a Georgia slattern because a London cutpurse went unhung. Each moment is the fruit of forty thousand years. The minute-winning days, like flies, buzz home to death, and every moment is a window on all time.” As mentioned earlier, Edith left public education in the tenth grade. According to her twin sister, it was only partially because they were needed at home during the depression. With three growing boys and four girls, the oldest sister’s child born out of wedlock, and one sister mentally challenged due to an accident, the family was needy. And their mother couldn’t say no to any troubled neighbors or homeless drifters who came asking for food. According to Ellen, Edith was their Dad’s favorite, like Eugene in the novels, and like Eugene, the twins were born when their mother was 42. Their mother, a typical German-Dutch lady in appearance, was a strict member of the Pilgrim Holiness church and proud of her Pennsylvania Dutch heritage. Well into their early adulthood, the twins often had to sneak out to go to the movies or change clothes away from home if they wanted to wear slacks. Even so, neighbors often served as informers. So, when Edith was elected to the May court, Ellen figured that her parents would be concerned about them becoming too worldly. And then they were pulled out of school. It wasn’t fair. Their brothers behaved badly, but mother overlooked that. She seemed to favor the boys. The teasing and rough housing described in Look Homeward Angel was like her family. In later years I learned that, like Eugene’s siblings, some of Mom’s brothers and sisters had anxiety and anger issues. Alcoholism was an occasional problem, too. One brother lost his wife and child during World War II to a richer man and fled to the West, never to return. Eugene “hated the house and all that went on there.” Mom seemed merely embarrassed by her family’s situation, And there was little food—the boys ate first, and Mom said there was often little left after that. A photo of the twins at around 13 years old is sad. They are skin and bones. It was not clear to me if her brothers worked in the 1930s before they were drafted in the early 1940s, but the girls were expected to help around the house. She never stated that she was embarrassed, but I could tell by the way she described her childhood. There was the same hopelessness that the Gant children felt, that nothing could change and that she had no control over her situation. Like Eugene, she saw members of her family as having no vision. School was the most important thing in her life, and she lost the opportunity. She connected with Wolfe, who held the same opinion on education. She saw him as one like herself who was able to overcome family obstacles and work toward his dream. When mom talked to me about her hometown, her stories were as perfectly descriptive as Wolfe’s were of Altamont. With the little formal education she had, I wonder what she thought as she read this novel so full of literary references from ancient times to more recent. When he wrote of a scene reminding him of a Peter Breughel painting, did she comprehend it?  Circumstances Change Mom was always an avid reader, but I think the genres and types of material she read was enhanced by her experience with the American School, which was focused on literature and provided a small library of famous works. Reading Wolfe would have brought back bitter memories, especially of loss and being eternally torn between the past and present. I imagine what it would have been like for her to leave Marion that last time—Dad driving and me, six weeks old, in her arms. Dad’s job would require some moving around for a year or so until he became senior enough on the railroad roster for a permanent location. We moved to a trailer in a small town about thirty miles away that first time, but Mom knew it would mean only occasional trips back home. Dad knew she’d be homesick, but he hoped her life could be better removed from the large, unstable family. Later years would prove him right. Her parents and siblings saw the world in false rose-colored glasses, in denial of their dysfunctional relationships, seeing dysfunction only outside the family in the close-knit community in which they lived. He finally earned a permanent assignment about 120 miles from her hometown, but it could have been a continent away. She never felt comfortable in her new setting. She’d been used to a house full of relatives and friends living nearby. She told me she thought that her lack of self-confidence was the reason why she had a hard time making friends. But as I grew older, I saw that, like Eugene, it was mostly that her interests and world view were so different from our neighbors. She didn’t neighbor much as conversation was strained, which alienated her. Eugene describes the alienation Mom felt. He says that as he’s reading Euripides, those all around him “…are sitting around eating fried food. “ We were the only ones on our street that hadn’t migrated there from West Virginia or Kentucky, and dad, a railroader, was the only father not working in a rubber factory. Although none of the mothers worked, they were the only couple with an only child. It was by choice. There was a cultural divide. For example, the fact that I (a girl even!) was going to college was perplexing to some and downright comical to many neighbors. Didn’t I want to get married? It was odd enough that I hadn’t dated until I was a high school senior. They weren’t aware of the house rule—education comes first. Some Look Homeward Angel readers have said that the sections of the book dealing with family illnesses and death are the best written. I wonder if those reminded Mom of when she was around seven years old and nearly died of scarlet fever. She told me how it scared Ellen at the time. The illness and death of Eugene’s brother is a pivotal point near the end of the book. To my knowledge, Mom didn’t attend the funeral of her older disabled sister who died at an early age of leukemia. If she didn’t, I’m sure she felt guilt, and the scenes Wolfe describes of the family were familiar and sad for her. The Wolfe family history on the mother’s side influenced family relationships. In my Mom’s case, it was the family history on the paternal side. Her father had seven siblings. Their well-to-do parents died at the same time from pneumonia when the children were young, and each received a decent inheritance. The others held on to theirs; grandfather lost his in a bad business deal soon after he came of age. After that, he was never as close to the others. He was, however, intelligent, having seen some of the world while serving in the Army in the Philippines and the Pacific before WWI. Mom always admired him and boasted about him as my father shook his head and smiled over the incongruity of it all. Maybe father Gant reminded her of her own father in that way. He never reached his potential but “could have been great” if he hadn’t lost his inheritance. Eugene said he felt like an exile in another land and a stranger in his own, and I think Mom felt that way when she visited back home every four to six months. She wrote to her father often, and we visited on holidays. In warm weather, her family members would stay inside reminiscing while their spouses held court outside in retreat. My father’s parents lived in the same town, but he was an only child, and their relatives lived in Southeastern Ohio. Eugene works his way out of the family by getting very involved in academic activities and joining many campus groups. Is that why Mom encouraged me to do that? She couldn’t herself. Like Eugene, she didn’t like work, preferring reading and daydreaming—imagining. For him, it was the drudgery of work. According to her, it was others telling her what to do—the loss of freedom to do as she wished yet again. “I’m glad I never had to work for anyone else; I couldn’t take orders from anyone,” she said. When WWII began, she tried two jobs. Each lasted for about two weeks—one as a munition’s packager and then a nurse’s aide. She excelled at typing and shorthand, but evidently never sought work as a secretary or couldn’t get one because of her lack of a high school diploma.  Epilogue Eugene wanted two things: to be loved and to be famous. Mom wanted to be understood and to make her father and others in her hometown proud. For that she lived vicariously through me. Her hometown was the center of her world as she grew up. Through books and films, she could imagine going away, but like Eugene, in her formative years she could really never leave. The descriptions of relationships—or lack thereof—with Jews and “Negroes” in Look Homeward Angel and Wolfe’s other works is especially troubling and will be discussed in a later post. It was hard to hear my grandfather and an uncle sometimes refer to these groups in discriminatory terms as well. The women in the family never did, and one sister eventually had an African American daughter-in-law whom she adored. But I found the same issues in that generation in my spouse’s family. Prejudice didn’t only exist in the South. Many of grandfather’s grandchildren had careers in social services helping the disadvantaged, including one who was active in civil rights in the 1960s. Times change. I hope my Mom ultimately felt that she was fortunate to leave her hometown and her situation even though she was often lonely. My father often reminded her of her good fortune. And I experienced a very different life than I would have. One of my cousins had been a star football player in high school and later a referee traveling around the state. He could have gotten a better job elsewhere in a bigger city, but the hold of the family, much like Eugene’s, kept bringing him back to his rural town. I could tell when I visited that he longed for a similar escape. Next Time Wolfe often stated that he was influenced by author James Joyce’s stream-of-consciousness writing style and it is evident in Of Time and the River with themes of life, death, and his perceptions of America in the 1920s and 1930s.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Archives

August 2020

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed