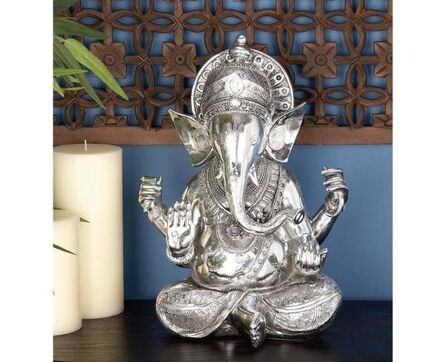

Lakshumi Lakshumi My father was stationed in India after V-J Day (Victory in Japan) in the fall of 1945. He wrote of many Indian traditions and ceremonies with great interest—V-J Day victory celebrations, funerals, and, although he never mentioned it by name, the Hindu festival of Diwali, which symbolizes the spiritual victory of light over darkness, good over evil, and knowledge over ignorance. This year Diwali will be celebrated around the world on Saturday, November 14. Celebrating Diwali Hindus hold many festivals throughout the year, but arguably the most widely observed is known by many names—Dipavali, Festival of Lights, Necklace of Lights—but it is commonly referred to as Diwali. The name is derived from Sanskrit, meaning “row or series of lights.” It occurs at the conclusion of summer harvest and welcomes the new moon, the darkest night of the Hindu calendar. The five-day pan-Hindu festival evolved over time from diverse local autumn harvest festivals throughout the Asia, which share spiritual significance while retaining local traditions. Associated with a variety of deities, traditions, and symbolism, the festival varies regionally, within various sects of Hinduism itself, and within the many other countries and religions where it is celebrated. Wikipedia provides comprehensive information on the festival with links describing the many terms and deities involved.  The Five-Day Celebration People dress in their finest clothes, illuminate the interior and exterior of their homes, light fireworks, and hold family feasts where gifts are shared. Day one celebrants begin cleaning and decorating their homes, and many decorate their floors as shown in the photo (left). Some geographic regions consider day two as the primary celebration day for Diwali. Other regions observe it on day three, the darkest night of the month, when it is an official holiday in about twelve countries. Day four is dedicated to the relationship between wife and husband, while day five is dedicated differently in communities. Some honor the bond between sister and brother while others emphasize craftsmen, offering prayers in their workspaces.  Ganesha Ganesha 'India 1945 In a November 1945 letter home, dad mentions the activities in Calcutta during Diwali, saying that it reminds him of a trip to a small village shortly after V-J Day. During his time at a rest camp in Ranikhet, he and two friends took a bus ride about thirty miles back in the mountains for an overnight stay in the town of Almora, located on a ridge at the southern edge of the Kumaon Hills nestled within higher peaks of the Himalayas, 226 miles from New Delhi. The population then was about thirteen thousand. They rarely saw American G.I.’s. They were in the midst of celebration that Tom described below. “They were celebrating V.J. day in a big way and we stayed overnight. We were the only G.I.s in town so you know we were the center of everything. The school had a parade in the afternoon and a big time that was odd to us. In the evening there were small pots of burning oil every place, on top of all the buildings, on the streets and most every place about three feet apart. Could look around the mountain and see the whole city at once. It was something to see. I think everyone in town was in the bazaar area, the market. We went up and there was Indian music everyplace, instruments I never saw before but made a lot of noise. It looked as if most of the crowd was around us, we had to go where they did. They were all yelling about the victory and the Americans. You don’t know how we felt. Felt way out of place but had quite a time…” Closer to Diwali, a November 13 letter home describes how the U. S. Army helped get into a festive mood during the holiday. A soon-to-be-held event at Calcutta’s Monsoon Square Garden announced that internationally known Neona Maya and her “troupe of traditional dancing girls will perform in Persian Costumes.” A World Traveler Describes a 1970s Diwali John J. Putnam decided to participate Divali (as he referred to it) in Chandrauti, a village of four thousand inhabitants on the Ganges. His host was Mukh Ram, a fisherman. Putnam begins his story on the day before Divali, and his story validates dad's years-later oral history of the festival. “The womenfolk mixed fresh batches of manure and mud to patch the walls of monsoon-pitted houses; men gathered under a pipal tree to gamble, casting cowrie shells, the fishermen and I went down at dusk to scrub the boats and set little clay lamps adrift. When we climbed back up the bluff, we found the village transformed into a vision of beauty. At windows, doors and the corners of houses flickered hundreds of ghee lamps, emplaced by the women. In the ruin of a room reduced to knee-high walls by the monsoon rains, Mukh Ram knelt before two small images. One depicted Lakshmi, goddess of wealth; the other Ganesha, the elephant-headed god. Mukh Ram lit lamps and garlanded the images with marigolds: ‘O Lakshumi! O Ganesha! Rid us of our troubles and raise the walls of our house which have fallen.’ Next door his brother struck his head against the earth: ‘May our problems cease!’” In reading for this post, I am again reminded of the deity Ganesha, elephant-headed son of Parvati and Shiva. I’ve always thought him delightful. Now that I've learned that he is recognized as the symbol of ethical beginnings and the remover of obstacles I’m going to buy a replica for my study. Sources Great Religions of the World, John J. Putnam, “Down the Teeming Ganges, Holy River of India”, National Geographic Society, 1978 Constance Jones, Indologist specializing in religious sociology whose work is often referenced. Ann Otto writes fiction based on factual as well as oral history. Her debut novel, Yours in a Hurry, about Ohioans relocating to California in the 1910’s, is available online at Amazon, Barnes & Noble, and Kindle. Her academic background is in history, English, and behavioral science, and she has published in academic and professional journals. She enjoys speaking with groups about all things history, writing, and the events, locations, and characters from Yours in a Hurry and her current projects, which include research about Ohio’s Appalachia in the 1920’s and a compilation of her father’s World War 2 letters. She blogs on history and writing and can be reached through the website, https://www.ann-otto.com/ , or at Facebook@Annottoauthor and www.Goodreads.com

2 Comments

|

Archives

August 2020

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed