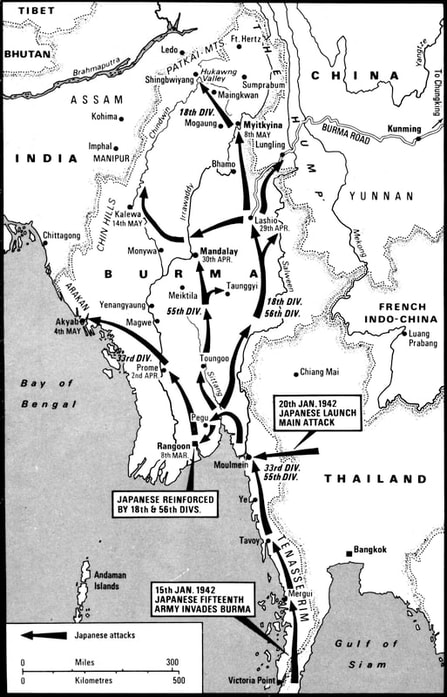

Map of China-Burma- India (CBI) Theater Map of China-Burma- India (CBI) Theater While typing my father’s letters, I often wondered why so little is written about his China-Burma-India (CBI) theater in WWII. The more I delved into the history, several reasons came to light. The British serving in Asia referred to campaigns in these countries as The Forgotten War, or front. Winning in Europe was the primary focus in 1942. Edward Fischer, a WWII CBI veteran, wrote a book about his experiences, The Chancy War, where he summarized feelings of the men concerning materials and manpower: “Over here, we are fighting a chancy war. If you ask the States for something, there is a slim chance you’ll get it and a greater chance you won’t. A chancy war!” The CBI theater was also relatively short-lived (early 1942 until October 1944) and its purpose provisional. To begin this series on the forgotten Southeast Asian front, it is helpful to discuss why America was involved to the extent it was. We had no direct interest in the countries involved, like Britain, which still ruled much of India, had interest in Burma, and had colonies elsewhere in that part of the world. The relationships among the Chinese, Japanese, Burmese, Indians, and British had a long, tenuous history. I’ve included a few sources at the end of the post if you want to read more about them, and you can find many more historical accounts by searching topics online. Let’s look briefly at each nation in 1942 at the beginning of American involvement. China Historians disagree on when WWII actually began. Was it after the WWI Paris Peace Treaty that disabled Germany, when Hitler marched into Poland, or, as author Max Hastings (see book cited below) opines, when the Japanese invaded China in 1931? By 1942, Chaing Kai-shek was the Chairman of the National Government of the Republic of China. However, over many years, the Chinese Communist Party had gained members under their leader, Zhou Enlai. Although the Allies pressured these leaders and their organizations to work together to rout the Japanese, a strained relationship remained throughout the war. If you read newspapers and books from the time and in the years immediately following the war, you would think that the allies won this front due to the ability of military leaders and service men and women of all nations to work together: the United States, Britain, India, China, Burma, Africa, Australia. But hindsight proves that many of the relationships were dysfunctional and decisions unwise. For all the work and resources involved, the results in Southeast Asia were not lasting. This appears to be part of the reason that there is less history about the CBI. Some question if it was a successful campaign given the future of most of these collaborating countries. In the case of the Chinese, Chaing Kai-shek was more concerned about keeping his nationalists in power, often stockpiling goods and military supplies for possible use later and being less than accommodating in providing Chinese troops until the United States threatened to stop assistance unless he became more cooperative. He often played the agitator with American and British leadership. India Britain’s goal was to protect India at all costs. Britain assumed the government of India in 1858, and in 1877 Queen Victoria was named Empress. Many in Britain, including wartime Prime Minister Winston Churchill, considered India “the jewel in the crown” of England. Like China, India’s government was somewhat unstable. Troubling spheres of influence representing several religions created conflicts. In 1942, sixty percent of the population in eleven provinces were part of British India. The other “Indian States” had a treaty with the British but were not subjects. India had been petitioning Great Britain for independence, or at least home rule for years, and a new anti-colonial activist, Mahatma Gandhi, was increasingly influential. He and others were quick to point to the many Indians being called to duty to protect what they saw as war to, in part, protect colonialism in Southeast Asia. Japan By the 1930s, Japan was in trouble. Its population was growing. It was land-locked and had few essential natural resources. Regardless of the country’s relatively small size, the government envisioned creating a unified Southeast Asia, another form of colonial imperialism fashioned after that of the Europeans. It started by taking Manchuria in September 1931. Burma Strategically in the center of countries in the region, Burma was quite important in Britain’s Southeast Asian plan to recapture Singapore and and protect India. By January 1942, Japanese forces had entered Burma from Thailand and controlled southern Burma. They took Rangoon in March and by April had closed the Burma Road to the Allies, cutting off transportation and communication lines between India and China. Japan eventually forced the British back into India and Stilwell’s American and Chinese forces back to China. By the end of May, Japan controlled all of Burma, Singapore, the Malay Peninsula, Sumatra, and Thailand. It should be noted that not all Burmese worked with the allies. Those seeking to break ties from British rule joined as the Burmese National Army and invaded their native country on the side of Japan in 1941. In March 1945, when it was clear that the Japanese were beaten, they switched sides, claiming Japanese mistreatment. Not until the spring of 1944 did troops in Northern Burma—Anglo-Indian, Chinese, and America’s Merrill’s Marauders—begin to turn the tide by capturing a key airstrip in the town of Myitkyina. The Burma Road was again open.  Why was America so involved in this Southeast Asia campaign? Although we had no direct ownership in this area of the world, America felt compelled to help the allies in Asia. We wanted to stop the Japanese in retaliation for Pearl Harbor, the Philippines, and other Pacific battles underway. We relied on natural resources in the area, like rubber and oil. Franklin Roosevelt’s earlier close family business ties in China influenced his desire to maintain a good relationship with that country. And, some believed that only a nation the size of China could effectively resist a Japanese threat to the rest of Asia. A critical challenge for the allies was the transport of goods and military between India and China through Burma. The Himalayas are the highest mountains in the world, and the Burmese jungles are arguably the densest. When the Burma Road closed in 1942, transports were mainly flown “over the hump” of the Himalayas. But the airplanes had to fly dangerously high to avoid attack from the Japanese airplanes from the Myitkyina airfield midway between Ledo, India and Kunming, China. Although many among the allies thought building a road through Burma was impossible, General Joseph Stilwell made it happen. His tenacity and the skills and sweat of many American troops, especially those of the Army Corps of Engineers, led to the opening of the Ledo Road between India and China and a link to the Burma Road. This ensured a gas pipeline and a road for trucks to supply China. United States Army leaders acknowledged that Stilwell had been given "one of the most difficult" assignments of any theater commander. In 1945, the Ledo Road was renamed the Ledo-Stilwell Road. My father played a part in this Burma story. I plan to share more of the history—and his story—in future posts. I’ve only begun to research, but here are some sources if you want to read further on the above. Websites: The End Run of GALAHAD https://www.soc.mil/ARSOF_History/articles/v2n1_end_run_galahad_page_1.html China-Burma-India Theater: Stilwell's Command Problems, Volume 2; By Charles F. Romanus Over the Hill and Far Away by Troy J. Sacquety Books and Journals Retribution: The Battle for Japan 1944-45; Max Hastings, 2008 Inside Asia by John Gunther; 1938-39 (Note: Asian cultures and the lead-up to WW2) “Our Impossible War”, Reader’s Digest October 1942, pp. 1-3 Stillwell and the American Experience in China, 1911-1945; Barbara Tuchman, 1970 Thailand, Burma, Laos and Cambodia: Modern Nations in Historical Perspective; Ed. Robin Winks, 1966 Asiatic Land Battles: Allied Victories in China and Burma Vol. 10 of The Military History of WW2; Trevor Nevitt Dupuy, 1963 The Last Lion: Winston Spencer Churchill, Volume 3: Defender of the Realm, 1940-1965; William Manchester and Paul Reid, 2012, pp. 416-508 The Chancy War: Winning in China, Burma, and India in World War II; Edward Fischer, 1991 Ann Otto writes fiction based on factual as well as oral history. Her debut novel, Yours in a Hurry, about Ohioans relocating to California in the 1910’s, is available online at Amazon, Barnes & Noble, and Kindle. Her academic background is in history, English, and behavioral science, and she has published in academic and professional journals. She enjoys speaking with groups about all things history, writing, and the events, locations, and characters from Yours in a Hurry and her current projects, which include a novel about Ohio’s Appalachia in the 1920’s and a compilation of her father’s World War 2 letters. She blogs about history and writing and can be reached through the website, https://www.ann-otto.com/ , or at Facebook@Annottoauthor and www.Goodreads.com

0 Comments

|

Archives

August 2020

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed