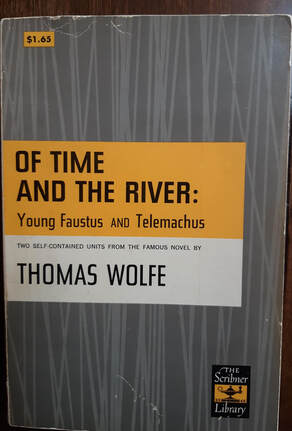

I don’t know what Mom thought of Wolfe’s second novel chronicling the Gant family published five years after Look Homeward Angel. My 1965 Scribner Library edition is titled Of Time and the River: Young Faustus and Telemachus, “two self-contained units from the famous novel.” As with the first novel, some sections resonated with her life. Surprisingly, some of Eugene and his sister Helen’s behavior and emotions reminded me, well, of me. The Subtitles First, I needed to understand the title and subtitles. Historically, time and the eternal flow of rivers are often themes in Wolfe’s writing. Young Faustus is easy to associate with Wolfe’s life if we de-emphasize the magic part of that ancient story. How is Eugene like Faustus? In Marlow’s play, Faustus is dissatisfied with his many interests and studies. Eugene, autobiographically Wolfe as a young man, is a loner like Faustus and seeks career paths that often frustrate him and lead him to despair. He shares Faustus’s angst over religion, and things often don’t turn out as he wishes or expects. His interpersonal relationships are sometimes non-transparent; he finds enjoyment in ridiculing others. He desperately searches for fulfillment. Like the mythological Telemachus, once Eugene’s father dies, he feels that he never knew him. In both Look Homeward Angel and death scenes in this novel, Wolfe provides elaborate character studies of the elder Gant describing his many contradictions—strong versus weak, compassionate, and caring versus brutal and egocentric as examples. Many of us feel similar uncertainty about our family—parents, grandparents, aunts, and uncles. It is human nature to wish we would have asked them more while they were still alive to better understand the contradictions. On Ancestors I wrote a novel based on several of my ancestors, some of whom I could have questioned before they died. But they died years ago, and being young when they were alive, I wasn’t interested in genealogy. I would have saved so much research time and would have had a richer story if I had. My mother-in-law, Doris, and her mother, Florence, should have dug deeper into their family history, too. Flo was born when her mother was older. She worshiped her sister, who was many years older. When Flo was about five years old, her mother told her that her sister died. She was too small to ask why her sister had just disappeared, but she never got over the incident and continually, in later life, mentioned to Doris how much she missed the sister to the point that Doris related the story to us often after her mother was gone. By the time I began going online to research our family lines, Doris was in later stages of Alzheimer’s. Flo’s sister didn’t die in the 1920s; she died in an Ohio nursing home in the 1960s. Given what Doris told us about her grandmother, a staunch and controlling Catholic, I can guess what happened. The sister was described as pretty and fun-loving, so either she chose to leave her strict environment, or she was shunned by her mother. It’s sad that I couldn’t tell Doris at that point and that the rest of us never got to know this colorful relative. My Mom and Doris were influenced by strong family members—Doris by a grandmother and my Mom by her mother and father. Eugene’s mother was obsessed by wealth, Mom’s and Doris’s by religion. Both told me that they were embarrassed by their lack of self-confidence. We can read lack of self-confidence in Eugene and his siblings as well.  The Wolfe family Old Kentucky Home in Asheville, circa 1910 The Wolfe family Old Kentucky Home in Asheville, circa 1910 Similarities How do I see myself in Eugene? He writes down everything he wants to do and agonizes over what he hasn’t done. He wants to experience everything, understand everyone. Throughout his works, he is trying to understand other human beings—all of them. He decides he wants to be a dramatist more than anything. Then he loses heart. He seems to lack focus until he is successful at writing. But he often struggles to find what to write, always falling back on his experiences. He also needs a mentor to help him focus and succeed, in his case, editor Maxwell Perkins. I’m also a note-taker and planner, agonizing about what I didn’t do or get done even though I’ve been able to live most of my dreams. I’ve also struggled with purpose. I loved my full-time career, but also dabbled in other interests that might have been second careers: college teaching, consulting, writing novels. For over ten years I did these things but lost energy around them. Nonfiction writing and community work are my passion. Those of us with the resources and support system to test our dreams, like Wolfe before us, are fortunate. I had many mentors along the way to help me focus and make decisions. In another similarity Mom’s favorite time of year was fall. You can tell by the descriptive detail that Wolfe gives to fall, especially the month of October, that he likes it, too. Eugene goes back to Altamont (Asheville) for the first time in years after his father dies in October. My favorite time is closer to spring, which he mentions more than once in his works comes with certainty and joy in April. In his early writings Wolfe leans to toward the pessimistic to favor spring. Eugene’s sister Helen reflects on each period of her life, and reflections remind me of mom. A girl in high school with hopes and dreams, in Mom’s case to become a teacher; thirsting for something different as she reached eighteen, finding solace in movie houses, being ashamed around peers because of her family’s station in life. Helen asks, “What is life about? We are all lying here in darkness in ten thousand little towns—waiting, listening, hoping—for what?” I believe Mom may have felt that same disappointment. The Gant siblings are disheartened throughout the two novels because things will not change. Until the time of father Gant’s death, he and Eliza control their children’s lives in various ways. One example is a new car that Eliza purchases just to have one. She never drives it and years later she still won’t let any of the children drive it. She has many excuses, one being that she is “…afraid you’d go and hurt yourself.” Similarly, none of my mother’s siblings ever learned to drive because their mother witnessed an automobile accident early in her life—probably around the 1920s. She had anxiety syndrome, and it left a permanent scar. I have never understood how her sons served in World War II with this handicap. Possibly because they were such physically strong specimen. Interpreting America Wolfe endeavors to explain his perceptions of America in his writing and increasing in this and in the last two of the autobiographical novels. Sections in this novel are described by author Philip Roth in this way: “…his sprawling consciousness gave rise to a tome of elegiac lyricism that was endlessly sustained by the raw yearning for an epic existence….” One of Wolfe’s quotes on America begins, “…we are so lost, so naked and so lonely in America.” How he came to this conclusion is clearer as we continue reading the novels and will be discussed in a later post. He originally titled Look Homeward Angel as Oh, Lost!. He describes Americans of the 1930s and their futile desire that everything will be all right if only some one thing would happen: they can take a trip, eat bran for breakfast, get introduced to a famous person, have a famous author discover their manuscript, or win admission to a famous school. Sound familiar? He provides lots of examples of American vanity which unnerve him. So true in America today as well. The 2020 pandemic has made many of us question how we spend our time—always doing, as Eugene’s sister Helen says, “useless things,” exhausting our energy when what we really want is “joy, love and beauty.”  Grandfather Pearl Darnell (left) circa 1930 Grandfather Pearl Darnell (left) circa 1930 Nostalgia Wolfe’s writing, like Marcel Proust’s, has been described as based on nostalgia. An example is the image Wolfe uses often and which I associate with my parents, that of a train whistle. As Eugene is waiting to leave Altamont at the end of the novel, he hears the wailing whistle of a distant train. He has heard it a thousand times in childhood and, now as then, it gives him desperate hope, a golden promise of something new. I don’t know if that is what my Mom thought when she heard the whistle and trains often in her small Midwest railroad town. Her father, brothers, father-in-law, and husband worked for the Erie Lackawanna Railroad. Trains and whistles were nostalgic for her and my father, and there is a railroad engine along with a wedding ring etched on their gravestone. They are buried in another small Ohio town under pine trees next to a former train track that has been converted into a park towpath. A little north of there, trains go through daily. When the wind is just right, I can hear the whistle in the middle of the night. It brings back memories of my engineers—both my father and the grandfather who stopped in town to see us on his layovers between western Ohio and eastern Pennsylvania. So this is one way that Eugene and Mom differ. For our family, the train whistle didn’t’ symbolize the new promise and way out. It represented and still represents a family heritage and nostalgia for other times. Regardless of similarities between my mother’s and my experiences and emotions and those of the Gant (Wolfe) family, I’d like to believe that Mom eventually felt that she had made peace with her earlier life. I wish she were here so I could ask her. Ann Otto writes fiction based on factual as well as oral history. Her debut novel, Yours in a Hurry, about Ohioans relocating to California in the 1910’s, is available online at Amazon, Barnes & Noble, and Kindle. Her academic background is in history, English, and behavioral science, and she has published in academic and professional journals. She enjoys speaking with groups about all things history, writing, and the events, locations, and characters from Yours in a Hurry and her current projects, which include research about Ohio’s Appalachia in the 1920’s and a compilation of her father’s World War 2 letters. She blogs on history and writing and can be reached through the website, https://www.ann-otto.com/ , or at Facebook@Annottoauthor and www.Goodreads.com

0 Comments

|

Archives

August 2020

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed