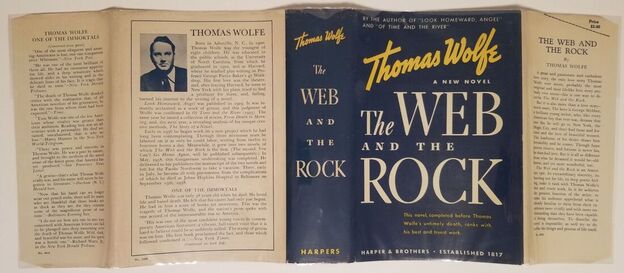

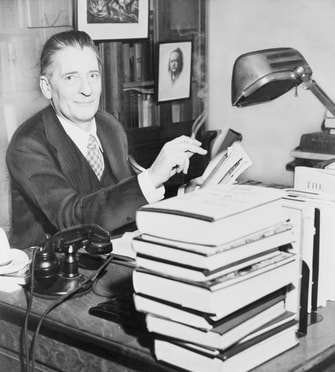

The posts about Thomas Wolfe’s novels continue with The Web and the Rock, the third in the series. The introduction in my 1960 Harper and Brothers Dell edition by author Richard Chase states that although the authors of Wolfe’s period praised his first two novels, over time this book and his next were viewed negatively. We need to remember that only the first two, Look Homeward Angel and The Web and the Rock, were written singly by Wolfe. The later works, as Gail Godwin states in her introduction of You Can’t Go Home Again (Scribner, 2011), were so “…spuriously ‘put together’ out of Wolfe’s packing cases of manuscripts by his last editor, Edward Aswell, that purists must refuse to consider them Wolfe’s creations.” Others disagree with her, including well-regarded Wolfe biographer David Herbert Donald.  Editor Maxwell Perkins Editor Maxwell Perkins I’m not a purist when it comes to a good story and have great respect for Max Perkins, who guided Wolfe, Ernest Hemingway, F. Scott Fitzgerald, and Elizabeth Kinnan Rawlings, among other notable authors to publication. Wolfe’s executor and friend approved Aswell’s publication of the works. That being said, The Web and the Rock was more difficult to read than the first two—wordy passages, repetitive descriptions, narratives and quarrels between the two main characters. But was this Aswell’s doing or the fact that this part of Wolfe’s veiled autobiography reflected a more turbulent period in his life, a first foray in the larger world? Or, as author Andre Dubus once noted in an interview, “There’s a lot of repetition in a lot of writers I love, probably because of their passions, fears, what we love as humans. It doesn’t bother me; it’s just unintentional.” This surely describes Wolfe. In this third novel, character and location names change, as does some of the family history. Eugene Gant becomes George Webber, perhaps as a reflection of the “web” of humanity mentioned in the title and throughout the book, and the Gants become the Joyners.  Ellen Jane and Edith circa 1941 Ellen Jane and Edith circa 1941 Similarities George continues Eugene’s predisposition to dependency on someone—his mother, a teacher, someone in his writing class, Esther Jack. And then over time he repudiates them, but later worries, “What will they think?” This is a shared trait among my mother’s family members, too. Was it a mindset created when the patriarch of both families suffered loss early in life and became estranged in some ways from their extended family members? Wolfe often admits that he writes in the James Joyce stream-of-consciousness style. His writing reminds me more of Marcel Proust’s. He shares with Proust the ability to observe people and capture them vividly in print. An example is his description of a stay in Munich in the late 1920s. Our family made a trip there in 2017, and his descriptions—the sights, sounds, smells and costumes—reflect our experiences decades removed. Wolfe said that capturing life vividly is what kept him interested in writing when he felt like giving up. Both authors were engrossed with memories. My mother was, too. Sometimes it was like she was living in the past, before leaving her childhood home. Like George’s Aunt Maw, mom repeated her stories often. I loved listening and can repeat them today, long after she passed away. As described in an earlier post, Mom began to feel like she didn’t fully belong in her biological family or in the new cultural environment after marriage and the move out of town. The Southern Experience Wolfe has a troubled relationship with the South. He is of the South but doesn’t wish to live there after experiencing New York City. Another Southern author of a similar opinion, Pam Durban, has stated “The South is rich for me as a place because of the tension there, not because of how much I love it, not because I am nostalgic for it. It’s because of the tension. Every aspect of it.” I sense Wolfe felt the same. Aunt Maw Joyner is the family member that George is closest to growing up. She is a link to the pre-Civil War and Civil War past. Through her repetitious stories, George and others learn about “…the South they did not know but…remembered.” From his relationship with her and his Uncle Mark, George becomes aware that Southerners in his family are very proud of their heritage, self-righteous, self-satisfied, and living at the base of society, unaware and inflexible in their knowledge of the world. As always, I’m often puzzled by Wolfe’s conflicting views and emotions concerning Blacks in his works. More on that in a future post on racism. We can see his predicament: He dislikes these character traits, but knows he fits the pattern. Perhaps he felt that escaping the South would make a difference. The last several pages of the novel are poetic, a discussion with himself—the Body and the Man—of times past. He hears noises and voices of lost kinsmen, long gone, in the mountains who say, “that was a good time then.” The novel ends with “But—you can’t go home again.” Which is chronologically the title of the next novel—and the topic of the next blog post. Note: The Center for the Study of Social Policy has decided to standardize the capitalization of “B” in Black in their writing when referring to people of African descent stating that this refers to not just a color but signifies a history and the racial identity of Black Americans. This and future posts reflect this standardization. Ann Otto writes fiction based on factual as well as oral history. Her debut novel, Yours in a Hurry, about Ohioans relocating to California in the 1910’s, is available online at Amazon, Barnes & Noble, and Kindle. Her academic background is in history, English, and behavioral science, and she has published in academic and professional journals. She enjoys speaking with groups about all things history, writing, and the events, locations, and characters from Yours in a Hurry and her current projects, which include research about Ohio’s Appalachia in the 1920’s and a compilation of her father’s World War 2 letters. She blogs on history and writing and can be reached through the website, https://www.ann-otto.com/ , or at Facebook@Annottoauthor and www.Goodreads.com

2 Comments

|

Archives

August 2020

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed