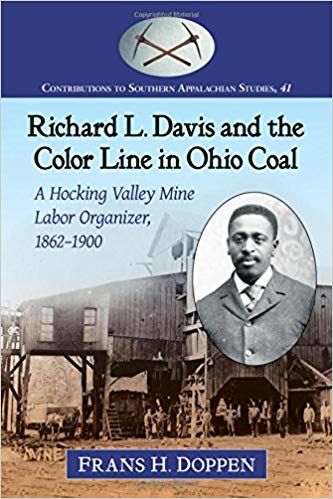

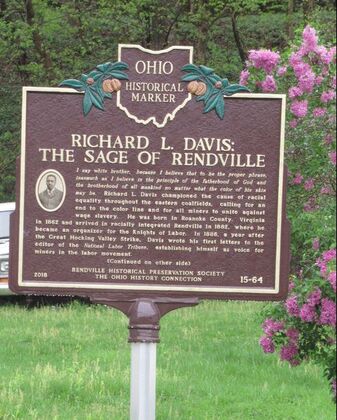

The history of the labor movement and African Americans in Southeast Ohio’s Little Cities of Black Diamonds are inseparable. Two of the emerging union’s internal problems were how confrontational they should be with owners and whether they should accept African Americans. Unique Ohio individuals were instrumental in African Americans gaining union acceptance here and nationally. I learned about this at an Ohio History Center seminar on coal miner history in The Little Cities of Black Diamonds where I purchased the book, Richard L. Davis and the Color Line in Ohio Coal: A Hocking Valley Mine Labor Organizer, 1862-1900 by Frans H. Doppen, which is part of the Contributions to Southern Appalachian Studies, 41 (McFarland & Company, Inc., 2016). Southern African Americans, like their white counterparts, hoped for better wages in the North. They were originally brought to the region as strikebreakers, although most were unaware of it before they arrived. Met with prejudice and violence, the labor movement eventually helped them gain acceptance. William Rend In 1879, Chicago businessman William Rend established the Rendville mine town east of Sunday Creek near Corning (see earlier post https://www.ann-otto.com/blog/appalachia-north for geography). Between 1880 and 1900, it was also the primary African American village in the Little Cities, celebrating Emancipation Day each September 22. Rend was described as a maverick mine owner and tended to side with minors in labor disputes. He not only refused to use black miners as strikebreakers but paid them the same as whites, which wasn’t common before unionization. The Lexington Tribune noted Rend’s philosophy in 1882: any man who wants to work, and is willing to work, is welcome to go into their mines regardless of any organization, color or creed. The colored and German miners would be paid the same as the old miners.  A former company town in the Little Cities A former company town in the Little Cities Contrasting Environments In the early 1890s the mining town of Congo was developed three miles west of Rendville. “Congo” was the nickname of an African American who traveled from Alabama in the 1880s to find work on the railroad in Ohio. Congo Mooney became a leader in the African American railroad workers’ camp that his fellow workers called “The Congo.” The Congo Mining company built forty company houses. For a time, it was thought that at some point Congo might be larger than Corning. But the big plans faded when a Columbus coal company took over the town and started updating the mine, including replacing miners with electric equipment. Life for miners in Congo was under company control. They were paid with company money and had to shop at the company store. They could be evicted from their company homes within five days of lay off, quitting, or being on strike. The community was fenced all around “like a prison,” primarily to keep merchants out of town. Regardless, Congo was known for labor peace and productivity. Over time, Congo would mine four hundred million tons of coal. There were two high hills in the town, called Hungarian Hill and Colored Hill. A picture of the large Sandy Creek Coal Company store in summer 1912 Congo shows many hammocks for sale hanging from the ceiling, men, some in work clothes and some in suits chatting in the corner and barefooted children in unkempt clothing lollygagging around the store, possibly to avoid the hot sun. Over time, the African American population moved on to Rendville or other communities.  Richard L. Davis Perhaps the most influential individual in the African American community at the time was Richard L. Davis. A well-known, passionate mine labor organizer, by 1898 he was known as the Sage of Rendville. ‘Dick’ Davis, as friends referred to him at the time, was born in Virginia but spent most of his adult life in Rendville. He became prominent in the growing mine labor movement and was twice elected to the National Executive Board of the United Mine Workers of America (UMWA), the only African American so honored. An example of the adversities he had to endure is a famous meeting in Corning, Ohio on August 22, 1895. Davis was invited to dinner with UMWA President Penna and other labor leaders at the upscale Mercer Hotel in Corning. When Davis sat down, a hotel employee approached and whispered in Davis’s ear that “colored men cannot eat here” because guests from West Virginia would be offended by his presence. He left, but the four labor leaders followed right behind him to the nearby Allen House, which served them. Several months later, Davis filed a claim for $ 500 in damages against the hotel owner. He was unsuccessful after several appeals. The judges noted that the Mercer’s owner had already been fined by the state. The Mercer Hotel incident was the first business violation of Ohio’s recently passed anti-discrimination law. Although some Little Cities newspapers continued to publish racist comments, the UMWA Journal continued to voice that “there have only been two races on this earth since the world began—the working race and the exploiting one.” Davis continued advocating strongly for the union, and during the national miners’ strike of 1987, Davis visited West Virginia and Alabama. He was continually targeted for his activities, especially as a leader after the union won the eight-hour work day (still six day a week) in April 1898. Ten- to twelve-hour days were common at the time. He was able to navigate the system; the culture didn’t seem to know how to relate to the only black leader in the union hierarchy. By 1900, the American Federation of Labor counted 40,000 African American’s as members.  Rendville Today Rendville Today Davis’s Legacy The New Lexington Tribune that had years earlier spoken badly of Davis noted upon his death in 1900 that Rendville was “robbed…of one of its most prominent citizens….” He eventually found work outside the mines and labor unions as constable of the village of Rendville. At that time, 301 African Americans of the 790 citizens were African Americans and nearly half of their 85 households owned their residencies. An additional 132 lived near the town. Davis’s monument is in the Rendville Cemetery. A UMWA Resolution at the January 17, 1900 convention recognized Davis as a “staunch advocate of the rights of those who toil, and his race….” Today, Rendville is Ohio’s smallest incorporated village, with a population of thirty-six. Post Script

Researching history provides interesting side notes. I found Adam Clayton Powell Senior’s time in Rendville interesting. Born in Virginia, his family moved to West Virginia for better wages. But they disliked the culture there and moved to Rendville in 1884. Powell noted that it was a lawless and ungodly place until a religious revival in the Methodist and Baptist churches drew so many converts that the saloons and gambling houses closed. He learned to appreciate his new community. He did so well at the small Rendville Academy that he left in 1888 to enroll at Virginia Union University to study Theology. The rest is history. Note: Information in this post is from Frans H. Doppen’s book described above and Images of America’s Little Cities of Black Diamonds by Jeffrey T. Darbee and Nancy A. Recchie (2009). Next time: Ohio: Cradle of Unionization Ann Otto writes fiction based on factual as well as oral history. Her debut novel, Yours in a Hurry, about Ohioans relocating to California in the 1910’s, is available on-line at Amazon, Barnes & Noble, Kindle, and at locations listed on her website at www.ann-otto.com. Ann’s academic background is in history, English, and behavioral science, and she has published in academic and professional journals. She enjoys speaking with groups about all things history, writing, and the events, locations, and characters from Yours in a Hurry. She is currently working on her next novel about Ohio’s Appalachia in the 1920’s and prepared for future works by blogging about a recent World War 2 European tour. She can be reached through the website, or on Facebook @Annottoauthor or www.Goodreads.com.

2 Comments

Larry Vargo

8/25/2020 08:01:58 pm

Read this with great interest and in fact felt compelled to share this. Actually grew up there (Congo) between ‘54-‘60. Recall these towns but did not appreciate the historical significance of the events that had transpired there. We lived on “Coloured Hill” but no one could give us any explanation for the name of that, nor of “White Hill”. Just thought it one of life’s peculiarities. By the time we moved there, any “coloured” folks were long gone and the mine was closed.

Reply

Ann Otto

8/26/2020 05:23:45 am

Thanks for your comments, Larry. Maybe Hungarian Hill eventually became known as White Hill? As you can tell from my posts about the Little Cities of Black Diamonds, I'm fascinated with all these towns that my dad talked about around where he grew up. Such rich history! Best, Ann

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

Archives

August 2020

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed